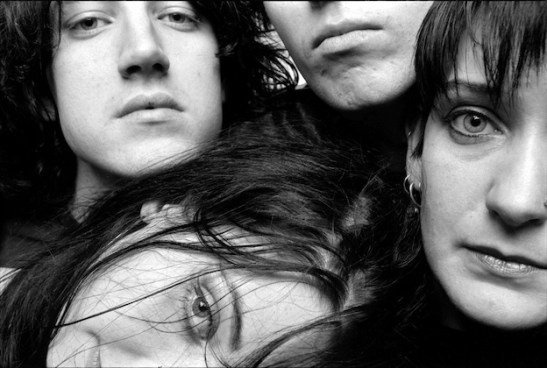

Isn’t Anything, Loveless, and EP’s 1988-91 Reissues – My Bloody Valentine – album reviews

For many in my age bracket, nothing was ever quite the same after the four chord intro to “Smells Like Teen Spirit,” but music historians know it was Loveless, not Nevermind, that became the real crucible in which 90’s alternative guitar rock was forged. Whereas Nirvana represented the synthesis and beatification of all things punk that came before them, My Bloody Valentine revealed a way forward. Loveless’ bludgeoning maelstrom of melodic noise, its warping guitar effects, and oil-slick thick, yet helium-light production values crystallized an aesthetic that would inform countless bands in both indie music and beyond.

As context, to truly understand MBV is to witness a band burdened by its own mythology. Front man Kevin Shields is typically imagined in one of two roles — either the obsessed audiophile whose quest for studio perfection on Loveless almost bankrupted label Creation Records or the Brian Wilsonesque recluse who spent two decades (and counting) trying to top that achievement, only to release nothing. It’s easy to forget that Shields’ first stroke of genius was recasting folk chords through guitar pedals and distorted, wall-of-sound amplification. His band’s entire collection, remastered and reexamined nearly 25 years later, reminds you both of the simplicity and majesty of this idea.

All told, the reissues include two versions of Loveless (one remastered from the original digital tapes and the other from previously lost 1/2-inch analog tapes), precursor LP Isn’t Anything and EPs 1988-1991, a compendium of all songs from band’s four EPs plus six previously unreleased tracks. As expected, the sound quality is magnificent (although not without its flaws — we’ll get to that in a minute). For me, the real revelation in exploring the Irish quartet’s complete catalog is that it allows those unfamiliar with the rest of MBV’s work to appreciate Loveless’ excellence in a broader context while simultaneously revealing that the band’s impact extended far past its finest hour. Loveless remains hallowed ground, but nearly everything leading up to it radiates with a similar, irrefutable aura.

In retrospect, the first few songs of Isn’t Anything (1988) are captivating but fairly straightforward — jangly verse/chorus guitar pop comprised of Jesus & The Mary Chain-style crunch and a warm, chaotic flood reminiscent of Dinosaur Jr.. But starting with track five, “No More Sorry,” MBV’s sound takes a quantum leap forward — guitarist Bilinda Butcher’s voice and guitar melt into a shimmering smear of impressionistic noise, distorting the air like heat rising off a highway. On “All I Need,” jagged peals of guitar feedback and ghostly voices collide in a fractured mosaic of melody and dissonance that is equal parts beautiful and frightening. From this point forward, Isn’t Anything is less a collection of pop songs than a series of Jackson Pollock-style sonic collages with arcs of sound splattered all over the place. It sounds unlike anything that came before it.

Too often overlooked as a stepping stone to MBV’s magnum opus, Isn’t Anything remains a magnificent album in its own right. Billy Corgan of the Smashing Pumpkins, who would attempt to mimeograph the Valentine’s sound to popular acclaim in the early 90’s, had this to say: “(In 1989), I heard this sound of this band and I couldn’t understand what I was listening to. I couldn’t understand how they were making the sound of the music they were making.” Few people could.

As he later revealed, Shields employed several techniques to achieve those aural illusions, including ostentatious multi-tracking of his and Butcher’s vocals, sampling his own guitar feedback, and extensively using his guitar’s tremolo bar to achieve that distinctive, warbly note-bending effect. Shields admitted: “People were thinking there’s hundreds of guitar tracks, but it’s actually got less guitar tracks than most people’s demo tapes have.” When these techniques coincided in just the right way with the right melody, the effect could be utterly transcendent.

Which brings us to what most consider describe the band’s crowning achievement, Loveless (1991). It’s a touchstone for so many musicians, not just in terms of remarkable technique and instrumentation but the way the guitars, vocals, and feedback all blend together to create an overall mood. There’s something primordial in the way these sounds — equal parts massive and fragile, gentle and excruciating — reverberate inside your ear and body. Some might argue that the long, arduous process of remastering Loveless is like touching up the ceiling of indie rock’s Sistine Chapel, with Michelangelo himself at the brush. As much as that monument is an expression of artistic beauty and an embodiment of the divine, Loveless, too, is a sort of revered document — it’s almost like you’re listening to Kevin Shields’ conversation with God.

Both remasters are treasures in their own right. For all its feedback and propensity towards loudness, Loveless has always been considered a “quiet” record; Shields attests that most of it is recorded at four to five dB below zero. But because CD players and most digital playback systems operate at their best in the top three dB, the album’s softer moments have never been done justice. According to Shields, the “remastered from digital tape” version remedies this problem by bumping the sound up to the higher, optimum level without clipping off the spikes in sound that connect listeners to the music — the ones you feel subconsciously more than hear.

Having listened to both this disc and the “remastered from analog tape” version (which Shields says is “more physical”), I’ll acknowledge the difference between the two is noticeable but difficult to articulate. Overall, what’s most exciting is that I’m able to pick out things I never could before on both versions — the dozen Butchers harmonizing on “When You Sleep,” the three-dimensionality of the flute-like trill at the end of “What You Want,” and the exquisite space between the electric rumble strip and acoustic strumming on “Sometimes.” All told, the dynamic range and detail on both discs is remarkable. Literally hundreds of descriptors have been used to describe these records, but oceanic is the one I’d choose. There’s a sense of vastness all around you and enormity beneath, but you feel buoyed up.

Of course, even with the Loveless remasters completed, controversy follows. One listener measured the EQ levels of the two CDs and discovered that disc 1 and disc 2 are actually mislabeled; the one we’re told is remastered from the original disc is in fact remastered from the analog tapes, and vice versa. There’s also an audible glitch on “What You Want” (at 2:46) in the analog remasters which, given Shields’ legendary perfectionism, is rather inexplicable. It’s only fitting that Sony Records, whom Shields asserts has been impeding progress on these remasters for a decade, manage to fuck it up somehow. Then again, an album with this sort of mystique is perhaps destined for these kinds of these oddities; it’s as though the original Loveless remains so perfect that fate sabotages any attempts to tamper with it.

EP’s 1988-91 feels less congruent since its a collection of four separate EPs, but it’s no less compelling. Tremolo EP gem “Honey Power” still represents the band at their serrated best, easily matching anything off of Loveless. It barrages listeners with blasts of feedback and dizzying melody for awhile, then unexpectedly drops it all away for a brief, soothing coda — perhaps the most gorgeous minute of sound My Bloody Valentine has ever laid to tape. It’s a trick also heard at the end of “Only Shallow,” “Swallow” and the EP version of “To Here Knows When,” in which you feel as though a raging hurricane has just passed overhead, and you’re now in the eye of the storm listening to the song’s muted fury from the inside out.

More so than any other band, My Bloody Valentine validates why many of us listen to difficult music. We desire it because it reminds us of our lives, and as M. Scott Peck once famously said, life is difficult. It’s brutally abrasive — it claws at you, wears you down, tests your patience in ways you never thought bearable. So does this music. But it’s achingly beautiful as well. There are fleeting moments when you are awestruck by its gorgeous textures, by the feeling of being held aloft in the palm of its hand.

Indeed, short of getting hit with 500 lbs of feathers or drifting into a deep sleep upon a bed of nails, its hard to describe the visceral, paradoxical quality of these albums. Whereas most of today’s music is meant for consumption while doing other things — exercising, working, commuting, conversing — there remains something resplendent about music that can be the focal point of your experience, rather than the soundtrack. Spend some time with these songs — struggling, suffering, resting, and reposing. You will be rewarded.

You have a great blog, and I’d like to submit some of my band’s music to you for review. Don’t see a place to do that.

Please contact me if you’re interested.

thetrapmusic@live.com

Thanks, Kevin..

Great review.

Great review, thanks. For audiophiles it is worth noting that disc 2 is more compressed. Listening on a high-end system most people would likely prefer disc 1 (tape remaster). More compression is good for radio, mp3 and casual listening, less is always better for serious listening – more air, more details, more organic – with the ethereal flow of this music it does make quite a difference in how it “feels”. I could certainly hear this before I analyzed the files visually. (extracted to FLAC). I still prefer my original LP version, though, but that’s just the magic of vinyl 🙂